July 1, 2016

GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE: a pandrogenous devotee of sex magick. Photo Peter Dibdin/Publicity image

GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE and TONY OURSLER have spent many years exploring paranormal phenomena through their artworks. Now, both have major exhibitions in New York – and suddenly they’re not alone in their interests.

Drugs, blood, caskets, fish and hair all feature in the arsenal of supplies enlisted for art by GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE. A few more, for variety’s sake: bones, a brass hand, dominatrix shoes and the discarded skin of a pet boa constrictor.

Best known as a musical dissident with the proto-industrial band Throbbing Gristle and later Psychic TV, BREYER P-ORRIDGE has made visual art for decades as part of a ritualistic practice in which boundaries tend to blur. The first transmissions of musical noise started in the 1970s, but art has been part of the project from several years before then to the present day. Work of the more recent vintage makes up the bulk of GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE: Try to Altar Everything, an exhibition on view at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York.

The Rubin show focuses on correspondences between global contemporaneity and historic cultures from areas around the Himalayas and India, and the show surveys, in an expansive fashion, BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s engagement with ideas from Hindu mythology and Nepal. Nepal is a favored haven away from the artist’s home in New York, but – as with most matters in BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s realm – worldly matters turn otherworldly fast.

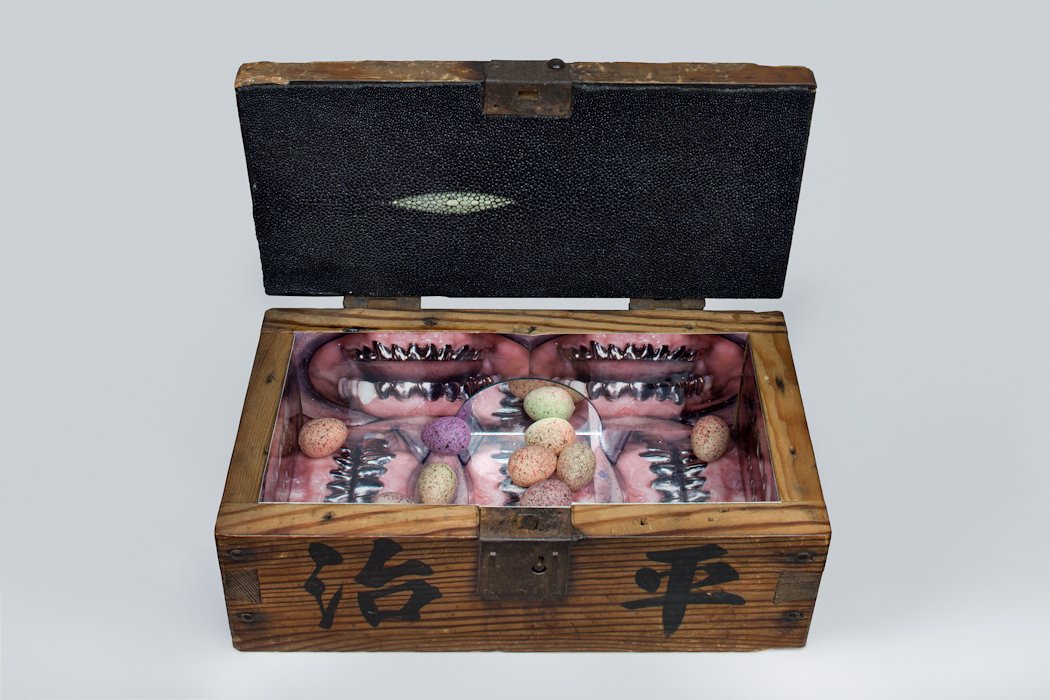

‘Reliquary’ by GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE. Photo Invisible Exports

Visitors to the exhibition are greeted by two large illuminated portraits of nude bodies on the surface of caskets standing on end, one belonging to the artist and the other to h/er late partner and muse LADY JAYE BREYER P-ORRIDGE. The unorthodox pronoun “h/er” is not a mistake but the preferred way to address the genderless existence of the pandrogyne, a state of male-female fusion the two were seeking to achieve by way of surgical incursions and rituals to combine souls. The undertaking was chronicled intimately in the 2011 documentary The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye, released to wide acclaim four years after LADY JAYE fell prey to cancer and died (or “left her body,” as GENESIS tells it). Now, Try to Altar Everything brings some of the couple’s collaborative artwork into the light.

Blood Bunny, made over 10 years until its completion in 2007, is a sculpture under glass of a wooden rabbit covered in blood. Hanging from its head is a ponytail made from LADY JAYE’s hair, bright blond in contrast to the dark blood all but black in its desiccated state. The source of it was needle pricks from injections of the powerful drug ketamine, which the couple took – and BREYER P-ORRIDGE reveres still – for its fabled out-of-body experiences.

“It’s such a powerful material that we don’t waste it – we use it. We’ve got little vials of blood in our refrigerator at home,” BREYER P-ORRIDGE says while staring the bunny down at the museum on a recent sunny afternoon.

‘Blood Bunny’: includes blood infused with ketamine. Photo Invisible Exports

Nearby are a small sculptural shrine with dried fish slathered in sparkles over an abstract mandala design (Feeding the Fishes, 2010) and an odd clock remade with fossil teeth, feathers and bits of gold alluding to alchemical forces (It’s All a Matter of Time, 2016).

Works of the sort in the show serve as reliquaries or tools for use in rituals rooted in a mixture of familiar religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, voodoo) and inclinations toward the more arcane realms of black magic and the occult.

“We’ve investigated lots of avenues and that includes occulture of various types,” says BREYER P-ORRIDGE, who uses the word “we” exclusively in reference to a sort of individual and collective self. Early learning from occult figures like ALEISTER CROWLEY and mysterious magical sects like the Ordo Templi Orientis led to a lifelong devotion to ritualistic practice that has expanded and evolved.

S/he speaks highly still of “sex magic, where the orgasm is the moment when all forms of consciousness in your mind are joined, temporarily, and therefore you can pass a message through.” And other ceremonial endeavors involving age-old symbols and codes continue to be part of a method of art-making that is as much about the making as the end result.

GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE ‘Feeding the Fishes’: a small sculptural shrine. Photo Invisible Exports

An essay in the catalog for the Rubin show refers to BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s earliest work’s dedication to “the ‘discovery of intention’, meaning it created and unearthed its message and relevance through performance, not before,” while characterizing h/er ritual-abetted communion with LADY JAYE as a “living, experimental work of art in the process”.

The exhibition, which continues through 1 August, arrives in the midst of a certain vogue for art attuned to occult practices. Last fall, a survey of demonic and deranged paintings by MARJORIE CAMERON, an associate of notorious rocket-scientist/occultist JACK PARSONS and film-maker KENNETH ANGER, showed at the gallery of prominent New York art maven JEFFREY DEITCH. A group show titled Language of the Birds: Occult and Art gathered work by the likes of BRION GYSIN, JORDAN BELSON, ANOHNI, LIONEL ZIPRIN, CAROL BOVE and many more (including BREYER P-ORRIDGE) in the 80WSE Gallery at New York University. Uptown at the American Folk Art Museum, a show titled Mystery and Benevolence: Masonic and Odd Fellows Folk Art drew visitors before closing in May.

Enough interest has been fostered and fanned out to make one wonder about the source of it all. Is it a yearning for art made for purposes other than mere aesthetic enterprise? A desired deferral to forces other than those proffered by markets and asset-class finance deals? A curiosity about creations devised with a mind for matters at play outside internal dialogues within just the art world itself?

TONY OURSLER, who has a new exhibition with paranormal proclivities on view at the Museum of Modern Art, says he can see the appeal of looking beyond the artistic pursuit for other forms of reason and rationale.

“A lot of people are trying to move into more social practices to find some relevance. It’s probably refreshing for people to see a certain kind of agency that can be offered in other practices,” the artist says.

OURSLER’s show is more playful and inclined toward levity and debunking than BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s. It includes parts of an immense archival collection related to stage magic and historical matters such as spirit photography and telekinetic mediums popular in the early 20th century, when notions of ghosts and transmissions from other worlds were very much part of the cultural conversation. The archive and a fanciful feature-length film, Imponderable, chart a peculiar history involving OURSLER’s own grandfather CHARLES FULTON OURSLER and his real-life dealings with characters including SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, HOUDINI and various spirit-world fixtures who turned out to be hucksters and frauds.

About the magnetism of such a subject, OURSLER speaks of an “unending interest in magical thinking and how it’s generated through media and various social means that led me back to these world views.”

He insists, too, that they are not as anachronistic as many might suspect. “Everyone walks around with a matrix of beliefs through which they view the world,” OURSLER says. “Statistically, if you look at America, it turns out roughly 60% of the population believes in ESP. One in three people do not believe in evolution. Forty percent of the public believes in UFOs. The rationalism we assume to be there might not, in fact, be there.”

BREYER P-ORRIDGE attributes rising interest in the occult to certain fleeting motivations. “Some of it is pure fashion, always,” s/he says. But the role of ritual and faith in its own ends can be a guide. After growing weary of the hierarchies and conscriptions of ceremonial magic as practiced early on (see: robes, chants, gestures with strict limitations and rules), “We thought: Do you need all the fancy theatrics or is there something at the core that makes things happen? Our experience tells us it’s just one or two things at the core. One of those is being able to reprogram one’s deep consciousness through repetition in ritual.”

When a working sense of ritual conjoins with the process of making art, the result might be differently invested. “When we walk around to galleries, we’re nearly always disappointed,” BREYER P-ORRIDGE says of art s/he sees around town. “Most of it is not about anything. It’s decorative at best and looks nice in penthouses. And now it’s gotten more corrupted because it’s like the stock market – people going around to advise people what to buy as an investment. You can’t trust the art world.”

To be trusted instead: “That strange reverberation that tells me what’s fascinating.”

Andy Battaglia

The Guardian

***

First Transmission (1982) by PSYCHIC TV (January 7, 2015)

Bight of the Twin (2014) by HAZEL HILL McCARTHY III (July 1, 2014)

Les yeux de GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE présentés à La Centrale (October 1, 2012)

La bible psychique de GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE (December 7, 2010)

‘Thee Psychick Bible’ A New Testameant By GENESIS BREYER P-ORRIDGE (October 27, 2009)